Asur Yönetiminden Kurtuluş

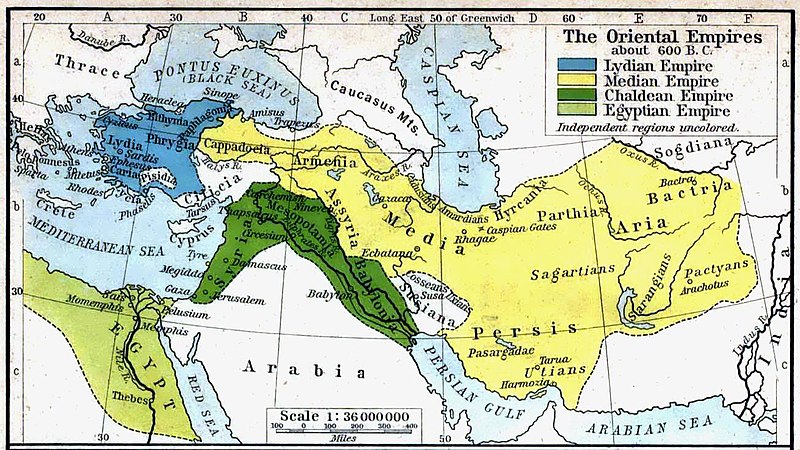

Yüzyıllar boyu süren Asur yönetimi süresince, Babil öne çıkan bir konumun üstünlüğünü yaşadı ve bunun aksi her durumda isyan etti. Ancak, Asurlular her zaman Babil'in bağlılığı, bazen ayrıcalıklarını artırarak bazen de askeri yöntemlerle, sağladılar. Bu durum son en güçlü Asur kralı Asurbanipal'in MÖ 627'de ölümüyle kesin olarak değişti ve Babil ertesi yıl Keldani Nabopolassar'ın önderliğinde isyan etti. Medlerin yardımıyla Ninova MÖ 612'de yağmalandı ve kralın tahtı tekrar Babil'e götürüldü

BABİL

Babil, Mezopotamya'da, adını aldığı Babil kenti etrafında MÖ 1894 yılında kurulmuş, Sümer ve Akad topraklarını kapsayan bir imparatorluktur.

Babil'in merkezi bugünkü Irak'ın El Hilla kasabası üzerinde yer almaktadır.

Kuzey Babil Devleti ise, Şırnak ilinin İdil ilçesi güneyinde Babil köyünde kurulmuştur.

Babil halkının büyük bir kısmı Sami ırkındandılar.

İnanç

Babilliler, eski halkların çoğu gibi birden fazla tanrıya taparlar, tanrıları üzerine kuşaklar boyu anlatılan düşsel öykülere inanırlardı. Bunların çoğu Sümer kaynaklıydı.

Evrenin ve insanların yaratılışını konu alan Sümer destanının kahramanı Gılgamış, söylenceye göre ölümsüzlük otunu bulmak için yola çıkar ve bu arayış sırasında binbir güçlükle karşılaşır. Serüven dolu yolculuğunun sonunda bulduğu otu, suların dibinden sinsice gelen bir yılan kayığından çalar. Bu öyküde Nuh Tufanı'nı anımsatan bir sel felaketinden söz edilir.

Tanrıları

Baş tanrıları Marduk idi. Babil efsanelerinde Marduk, ejderha Tiamat ile dövüşüp onu yener. Yeri, göğü ve insanoğlunu yarattığına inanılan Marduk'un yeryüzündeki temsilcisi kraldı. Marduk dışında toprak, su, gökyüzü, Güneş ve Ay tanrıları gibi tanrılara tapılırdı. Asurlular da büyük ölçüde Sümerler'in ve Babilliler'in dinleriyle tanrılarını paylaşıyorlardı. Ama, en büyük tanrıları adını imparatorluğun başkentine verdikleri Asur'du. Hem Babilliler hem de Asurlular'ın baş tanrıçası ise Eski Yunanlar'ın aşk tanrıçası Afrodit'e çok benzeyen İştar'dı.

Yazı ve Bilim

Sümer yazısı bilinen en eski yazıdır. Sümerler kil tabletleri, üstüne yazı yazdıktan sonra pişirirlerdi. Arkeolojik kazılar sırasında, bazıları 5000 yıllık olan binlerce tablet bulunmuştur. İlk yazı karakterlerini resimler oluşturuyordu. Bu resimler yavaş yavaş, Babilliler'in ve Asurlular'ın kullandıkları çivi yazısına dönüştü. Bu yazı biçiminde, kavramları belirtmek için köşeli simgeler kullanılırdı. Bulunan tabletlerin üzerindeki yazılar din, matematik, yasalar, bilim ve başka konularla ilişkindir. Matematikte, açılar konusunda bir tam dönüşü 60 birime bölmüşlerdir.

Babil Kulesi

Babil KulesiBabil Kulesi (İbranice: מגדל בבל Migdal Bavel), Tevrat'ta, Kur'an'da ve dünyanın birçok bölgesinde yerel efsanelerde bahsi geçen, tanrıya ulaşmak için inşa edilen kule.

Yahudi ve Hristiyan kaynaklarında

Tanah ve Eski Ahit hemen hemen aynı olduğu için her iki dinde Babil bahsi aynıdır. Babil kulesinden Tevrat'ın Yaratılış (Tekvin) kısmında bahsedilir.

« ... ve bütün dünyanın sözü bir, dili birdi. Şarktan göçtükleri zaman Sinear (sümer) diyarında bir ova buldular, orada oturdular. Birbirlerine 'gelin kerpiç yapalım, onları iyice pişirelim. Onların taş yerine kerpiçleri, harç yerine ziftleri vardı. Yeryüzünde dağılmayalım diye kendimize bir şehir, başı göğe erişecek bir kule yapalım' dediler. Ve ademoğullarının yapmakta olduğu şehri ve kuleyi görmek için Rab* indi. Onlar bir kavm, hepsinin tek dili var. Gelin inelim, birbirlerinin dilini anlamasınlar diye onların dilini karıştıralım. Rab onları oradan dağıttı ve şehri bina etmeyi bıraktılar. Bundan dolayı onun adına Babil dendi »

Efsaneye göre tanrı kendisine ulaşmaya çalışan insanların kendini beğenmişliğine kızar ve o zamana kadar aynı dili konuşmakta olan insanların dillerini karıştırarak birbirlerini anlamalarını engeller. Kulenin yıkılışı Tevrat'ta anlatılmaz ancak Jubilees veya Leptogenesis olarak bilinen Yahudi belgelerinde anlatılır.

Dini bir bakış açısıyla bu öykü sıklıkla insanın kusurluluğunu, tanrının kusursuzluğu ile kıyaslamak ve dünyadaki yüzlerce dilin kökenini açıklamak amacıyla kullanılır.

İslami Kaynaklarda

İsmi verilmemekle beraber Kur'an'da Babil Kulesi'ne benzer bir kuleden bahsedilir. Hikaye Tevrat'taki ile benzer olmasına rağmen Babil'de değil, Musa'nın yaşadığı dönemde Mısır'da geçer. Firavun Haman'a, kendisine kilden bir kule inşa etmesini, çıkıp Musa'nın tanrısına bakacağını söyler.

Kur'an'da Babil şehrinden Bakara Suresi, 102. ayette bahsedilir. Harut ve Marut isimli iki melek, insanları imtihan etmek için Allah tarafından Babil'e gönderilirler. Burada insanlara sihir öğretirler. Melekler sihrin küfür olduğunu söyledikleri halde insanlar sihir öğrenmekte ısrar ederler ve karı-kocayı ayırmaya yarayan sihirler öğrenirler.

Babilden Yakut el-Hamavi'nin yazmalarında ve Lisan el-Arab'da bahsedilir. Öyküye göre tüm insanlar rüzgarın önüne katılarak bir yerde toplanırlar. Buraya sonradan Babil denir. Babil'de insanlara Allah tarafından değişik lisanlar tahsis edilir ve yeniden rüzgarla geldikleri yerlere dağıtılırlar.

9. yy İslam tarihçilerinden el-Tabari'nin "Peygamberler ve Krallar Tarihi" adlı eserinde daha detaylı bilgi verilir. Öyküye göre Nimrod Babil'de bir kule inşa ettirir. Süleyman bu kuleyi yıkar ve o zamana kadar aynı dili konuşan insanların dilini 72'ye ayırır. 13. yy. İslam tarihçilerinden Ebu el-Fida da aynı öyküden bahseder ve İbrahim'in atası Hud'un kendi dilini (İbranice) muhafaza etmesine izin verildiğini ekler. Zira Hud kulenin inşasına katılmamıştır.

BABİLİN ASMA BAHÇELERİ

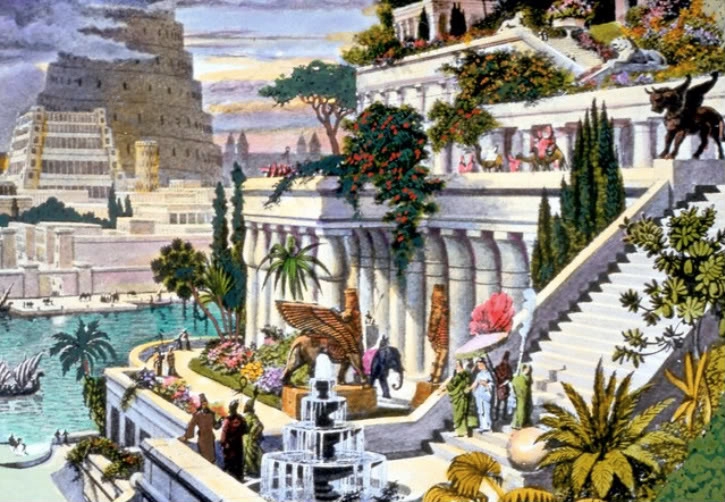

Babil'in Asma Bahçeleri, Dünyanın Yedi Harikası'ndan biridir. MÖ 7. yüzyılda Babil kralı Nebukadnezar tarafından yaptırılmıştır. Babil'in çorak Mezopotamya çölünün ortasında; ağaçlar, akan sular ve egzotik bitkilerin bulunduğu çok katlı bir bahçedir. Coğrafyacı Strabon'un 1. yüzyıldaki tanımına göre:

"Bahçeler birbiri üzerinde yükselen kübik direklerden oluşuyordu. Bunların içleri çukurdu ve büyük bitkilerin ve ağaçların yetişebilmesi için toprakla doldurulmuştu. Kubbeler, sütunlar ve taraçalar pişmiş tuğla ve asfalttan yapılmıştı. Yüksekteki bahçeleri sulamak için Fırat Nehri'nden zincir pompalarla su yukarılara çıkarılıyordu. Bu şekilde üst seviyelere taşınan su, bahçeleri sulayarak teraslardan aşağıya doğru akıyordu"

Söylenceye göre, Nebukadnezar bu yapıyı sıla hasreti çeken karısı Semiramis için yaptırmıştır. Semiramis, Medes kralının kızıdır. Mezopotamya'nın düz ve sıcak ortamı onu bunalıma itmiş, kral da karısının hasretini sona erdirmek için yapay dağların olduğu, suların aktığı yemyeşil bir bahçe yaptırmıştır. Bu yüzden bazen Semiramis'in asma bahçeleri olarak da anılır.

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or the Chaldean Empire was a period of Mesopotamian history which began in 626 BC and ended in 539 BC.[1] During the preceding three centuries, Babylonia had been ruled by their fellow Akkadian speakers and northern neighbours, Assyria. Throughout that time Babylonia enjoyed a prominent status. The Assyrians had managed to maintain Babylonian loyalty through the Neo-Assyrian period, whether through granting of increased privileges, or militarily, but that finally changed in 627 BC with the death of the last strong Assyrian ruler, Assurbanipal, and Babylonia rebelled under Nabopolassar the Chaldean the following year. In alliance with the Medes, the city of Nineveh was sacked in 612 BC, and the seat of empire was again transferred to Babylonia. This period witnessed a great flourishing of architectural projects, the arts and science.

Neo-Babylonian rulers were deeply conscious of the antiquity of their heritage, and pursued an arch-traditionalist policy, reviving much of their ancient Sumero-Akkadian culture. Even though Aramaic had become the everyday tongue, Akkadian was restored as the language of administration and culture. Archaic expressions from 1,500 years earlier were reintroduced in Akkadian inscriptions, along with words in the now-long-unspoken Sumerian language. Neo-Babylonian cuneiform script was also modified to make it look like the old 3rd-millennium BC script of Akkad.

Ancient artworks from the heyday of Babylonia's imperial glory were treated with near-religious reverence and were painstakingly preserved. For example, when a statue of Sargon the Great was found during construction work, a temple was built for it—and it was given offerings. The story is told of how Nebuchadnezzar in his efforts to restore the Temple at Sippar, had to make repeated excavations until he found the foundation deposit of Naram-Suen, the discovery of which then allowed him to rebuild the temple properly. Neo-Babylonians also revived the ancient Sargonid practice of appointing a royal daughter to serve as priestess of the moon-god Sin.

We are much better informed about Mesopotamian culture and economic life under the Neo-Babylonians than we are about the structure and mechanics of imperial administration. It is clear that for Mesopotamia the Neo-Babylonian period was a renaissance. Large tracts of land were opened to cultivation. Peace and imperial power made resources available to expand the irrigation systems and to build an extensive canal system. The Babylonian countryside was dominated by large estates, which were given to government officials as a form of pay. These estates were usually managed through local entrepreneurs, who took a cut of the profits. Rural folk were bound to these estates, providing both labor and rents to their landowners.

Urban life flourished under the Neo-Babylonians. Cities had local autonomy and received special privileges from the kings. Centered on their temples; the cities had their own law courts, and cases were often decided in assemblies. Temples dominated urban social structure, just as they did the legal system, and a person's social status and political rights were determined by where they stood in relation to the religious hierarchy. Free laborers like craftsmen enjoyed high status, and a sort of guild system came into existence that gave them collective bargaining power.

Neo-Babylonian dynasty

Dynasty XI of Babylon (Neo-Babylonian)- Nabu-apla-usur 626 – 605 BC

- Nabu-kudurri-usur II 605 – 562 BC

- Amel-Marduk 562 – 560 BC

- Neriglissar 560 – 556 BC

- Labaši-Marduk 556 BC

- Nabonidus 556 – 539 BC

Nabopolassar 626 BC – 605 BC

Nabopolassar was able to spend the next three years undisturbed, consolidating power in Babylon itself, due to the brutal civil war between the Assyrian king Ashur-etil-ilani and his brother Sin-shar-ishkun in southern Mesopotamia.

However in 623 BC, Sin-shar-ishkun killed his brother the king, in battle at Nippur, seized the throne of Assyria, and then set about retaking Babylon from Nabopolassar. Nabopolassar resisted repeated attacks by Assyria over the next seven years, and by 616 BC, he was still in control of southern Mesopotamia. Assyria, still riven with internal strife, had by this time lost control of its colonies, which had taken advantage of the various upheavals to free themselves.

Nabopolassar marched his army into Assyria proper in 616 BC and attempted to besiege Assur and Arrapha, but was defeated on this occasion.

Nabopolassar made alliances with other former subjects of Assyria, the Medes, Persians, Elamites and Scythians.

In 615 and 614 BC attacks were made on Assur and Arrapha and both fell. During 613 BC the Assyrians seem to have rallied and repelled Babylonian and Median attacks. However in 612 BC Nabopolassar and the Median king Cyaxares led a coalition of forces including Babylonians, Medes, Scythians and Cimmerians in an attack on Nineveh, and after a bitter three-month siege, it finally fell. Babylon retained control of Assyria and its northern and western colonies.

An Assyrian general, Ashur-uballit II, became king of Assyria, and set up a new capital at Harran. Nabopolassar and his allies besieged Ashur-uballit II at Harran in 608 BC and took it; Ashur-uballit II disappeared after this.

The Egyptians under Pharaoh Necho II had invaded the near east in 609 BC in a belated attempt to help their former Assyrian rulers. Nabopolassar (with the help of his son and future successor Nebuchadnezzar II) spent the last years of his reign dislodging the Egyptians (who were supported by Greek mercenaries and probably the remnants of the Assyrian army) from Syria, Asia Minor, northern Arabia and Israel. Nebuchadnezzar proved to be a capable and energetic military leader, and the Egyptians and their allies were finally defeated at the battle of Carchemish in 605 BC.

Nebuchadnezzar II 604 BC – 562 BC[edit]

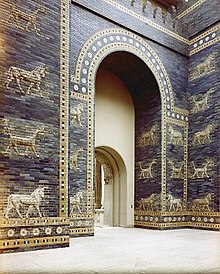

Nebuchadnezzar II became king after the death of his father.Nebuchadnezzar was a patron of the cities and a spectacular builder. He rebuilt all of Babylonia's major cities on a lavish scale. His building activity at Babylon was what turned it into the immense and beautiful city of legend. His city of Babylon covered more than three square miles, surrounded by moats and ringed by a double circuit of walls. The Euphrates flowed through the center of the city, spanned by a beautiful stone bridge. At the center of the city rose the giant ziggurat called Etemenanki, "House of the Frontier Between Heaven and Earth," which lay next to the Temple of Marduk.

A capable leader, Nabuchadnezzar II, conducted successful military campaigns in Syria and Phoenicia, forcing tribute from Damascus, Tyre and Sidon. He conducted numerous campaigns in Asia Minor, in the "land of the Hatti". Like the Assyrians, the Babylonians had to campaign yearly in order to control their colonies.

In 601 BC Nebuchadnezzar II was involved in a major, but inconclusive battle, against the Egyptians. In 599 BC he invaded Arabia and routed the Arabs at Qedar. In 597 BC he invaded Judah and captured Jerusalem and deposed its king Jehoiachin. Egyptian and Babylonian armies fought each other for control of the near east throughout much of Nebuchadnezzar's reign, and this encouraged king Zedekiah of Judah to revolt. After an 18 month siege Jerusalem was captured in 587 BC, thousands of Jews were deported to Babylon and Solomon's Temple was razed to the ground.

Nebuchadnezzar fought the Pharaohs Psammetichus II and Apries throughout his reign, and during the reign of Pharaoh Amasis in 568 BC it is speculated that he may have set foot in Egypt itself.

By 572 Nebuchadnezzar was in full control of Babylonia, Assyria, Phoenicia, Israel, Philistinia, northern Arabia and parts of Asia Minor.

Amel-Marduk 562 BC – 560 BC[edit]

Amel-Marduk was the son and successor of Nebuchadnezzar II. He reigned only two years (562 – 560 BC). According to the Biblical Book of Kings, he pardoned and released Jehoiachin, king of Judah, who had been a prisoner in Babylon for thirty-seven years. Allegedly because Amel-Marduk tried to modify his father's policies, he was murdered by Neriglissar, his brother-in-law.Neriglissar 560 BC – 556 BC[edit]

He conducted successful military campaigns against Cilicia, which had threatened Babylonian interests. Neriglissar however reigned for only four years, being succeeded by the youthful Labashi-Marduk. It is unclear if Neriglissar was himself a member of the Chaldean tribe, or a native of the city of Babylon.

Labashi-Marduk 556 BC[edit]

Labashi-Marduk was a king of Babylon (556 BC), and son of Neriglissar. Labashi-Marduk succeeded his father when still only a boy, after the latter's four-year reign. He was murdered in a conspiracy only nine months after his inauguration.[citation needed] Nabonidus was consequently chosen as the new king.Nabonidus 556 BC – 539 BC[edit]

Nabonidus's (Nabû-na'id in Babylonian) noble credentials are not clear, although he was not a Chaldean but from the Assyrian city of Harran. He says himself in his inscriptions that he is of unimportant origins.[2] Similarly, his mother, Adda-Guppi,[3] who lived to high age and may have been connected to the temple of the Akkadian moon god Sîn in Harran; in her inscriptions does not mention her descent. His father was Nabû-balatsu-iqbi, a commoner.[4]For long periods he entrusted rule to his son, Prince Belshazzar. He was a capable soldier but poor politician. All of this left him somewhat unpopular with many of his subjects, particularly the priesthood and the military class.[5]

The Marduk priesthood hated Nabonidus because of his suppression of Marduk's cult and his elevation of the cult of the moon-god Sin.[6][7] Cyrus portrayed himself as the savior, chosen by Marduk to restore order and justice.[8]

To the east, the Persians had been growing in strength, and Cyrus the Great was very popular in Babylon itself, in contrast to Nabonidus.[9][10]

A sense of Nabonidus's religiously-based negative image survives in Jewish literature, in Josephus, for example.[11] Though in thinking about that image, we should bear in mind that the Jews initially greeted the Persians as liberators. Cyrus sent the Jewish exiles back to Israel from the Babylonian Captivity.[12]Although the Jews never rebelled against the Persian occupation,[13] they were restive under the period of Darius I consolidating his rule,[14] and under Artaxerxes I of Persia, [15][16] without taking up arms, or reprisals being exacted from the Persian government.

Achaemenids and later rulers of Babylon[edit]

The Medes, Persians and Mannaeans, among others, were Indo-European peoples who had entered the region now known as Iran c. 1000 BC from the steppes of southern Russia and the Caucasus mountains. For the first three or four hundred years after their arrival they were largely subject to the Neo Assyrian Empire and paid tribute to Assyrian kings. After the death of Ashurbanipal they began to assert themselves, and Media had played a major part in the fall of Assyria.Persia had been subject to Media initially. However, in 549 BC Cyrus, the Achaemenid king of Persia, revolted against his suzerain Astyages, king of Media, at Ecbatana. Astyages' army betrayed him to his enemy, and Cyrus established himself as ruler of all the Iranic peoples, as well as the pre-Iranic Elamites and Gutians.

In 539 BC Cyrus invaded Babylonia. Nabonidus sent his son Belshazzar to head off the huge Persian army, however, already massively outnumbered, Belshazzar was betrayed by Gobryas, Governor of Assyria, who switched his forces over to the Persian side. The Babylonian forces were overwhelmed at the battle of Opis. Nabonidus fled to Borsippa, and on 12 October, after Cyrus' engineers had diverted the waters of the Euphrates, "the soldiers of Cyrus entered Babylon without fighting." Belshazzar in Xenophon is reported to have been killed, but his account is not held to be reliable here.[17] Nabonidus surrendered and was deported. Gutian guards were placed at the gates of the great temple of Bel, where the services continued without interruption. Cyrus did not arrive until the 3 October, Gobryas having acted for him in his absence. Gobryas was now made governor of the province of Babylon.

Cyrus now claimed to be the legitimate successor of the ancient Babylonian kings and the avenger of Bel-Marduk, who was assumed to be wrathful at the impiety of Nabonidus in removing the images of the local gods from their ancestral shrines, to his capital Babylon. Nabonidus, in fact, had excited a strong feeling against himself by attempting to centralize the religion of Babylonia in the temple of Marduk at Babylon, and while he had thus alienated the local priesthoods, the military party despised him on account of his antiquarian tastes. He seems to have left the defense of his kingdom to others, occupying himself with the more congenial work of excavating the foundation records of the temples and determining the dates of their builders.

The invasion of Babylonia by Cyrus was doubtless facilitated by the existence of a disaffected party in the state, as well as by the presence of foreign exiles like the Jews, who had been planted in the midst of the country. One of the first acts of Cyrus accordingly was to allow these exiles to return to their own homes, carrying with them the images of their gods and their sacred vessels. The permission to do so was embodied in a proclamation, whereby the conqueror endeavored to justify his claim to the Babylonian throne. The feeling was still strong that none had a right to rule over western Asia until he had been consecrated to the office by Bel and his priests; and accordingly, Cyrus henceforth assumed the imperial title of "King of Babylon."

Babylon, like Assyria, became a colony of Achaemenid Persia.

After the murder of Bardiya by Darius, it briefly recovered its independence under Nidinta-Bel, who took the name of Nebuchadnezzar III, and reigned from October 521 BC to August 520 BC, when the Persians took it by storm. A few years later, in 514 BC, Babylon again revolted and declared independence under the Armenian King Arakha; on this occasion, after its capture by the Persians, the walls were partly destroyed. E-Saggila, the great temple of Bel, however, still continued to be kept in repair and to be a center of Babylonian patriotism. Babylon remained a major city until Alexander the Great destroyed the Achaemenid Empire in 332 BC. After his death, Babylon passed to the Seleucid Empire, and a new capital named Seleucia was built on the Tigris about 40 miles north of Babylon (10 miles south of Baghdad). Upon the founding of Seleucia, Seleucus I Nicator ordered the population of Babylon to be deported to Seleucia, and the old city fell into slow decline. The city of Babylon continued to survive until the 2nd or 3rd century AD. An adjacent town developed which is today the city of Hillah in Babylon Province, Iraq.

Babylonia remained under the control of the Parthians, and later, Sassanians until about 640 AD, when it was conquered by the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate. It continued to have its own culture and people, who spoke varieties of Aramaic, and who continued to refer to their country as Babylon (Babeli) or Erech (Iraq). Some examples of their cultural products are often found in the Mandaean religion, and the religion of the Babylonian prophet Mani. From the 1st and 2nd centuries AD the Assyrians and Babylonians began to adopt Christianity, and the province of Babylon became a seat of a bishopric of the Church of the East until the 17th century. Neo-Aramaic-speakers exist today as a small minority only in northern Iraq (Assyria). Despite being the minority, the Assyrians remained Christians and many were killed as a result. Arabic had become the main language in Babylonia by the 9th century, when the region was the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder